Scandal, Shipwreck, and Salvation in Seventeenth-Century Japan

New York: Columbia University Press, 2013

Ko wa sutetsu kokoro o dani mo hōrasaji to mo omoedomo ana u yo no naka

My child I’ve given up;

Nakako’s father Nakanoin Michikatsu, lamenting the exile of his daughter

but my love for her, at least,

I’ll not let go;

yet oh! What a wretched world

that I must even think such things.

A noblewoman born in sixteenth-century Japan had three possible life courses: marriage, palace service, or a convent. Women also often moved from one status to another, becoming nuns after the death of a husband, lover, or powerful male protector. Nakanoin Nakako (1591?-1671) could have been just such a model woman. As a child of about ten, she entered service in the imperial palace, where her duties included waiting upon Emperor GoYōzei (1571–1617; r. 1586–1611). If her life had gone according to plan, she might have brought honor to her family one day by giving birth to an imperial child, then retiring to a convent after the emperor’s death. Instead, Nakako became embroiled in a sex scandal. She and several other imperial concubines consented to assignations with male courtiers, they went to view open-air performances of kabuki dancing, and they all enjoyed drinking together at parties that are described as orgies of indiscriminate couplings. When the emperor discovered what they had been up to, he was outraged and demanded that the guilty courtiers and concubines alike be “executed, painfully, and before mine own eyes.” But the savage punishment he called for was unprecedented in court society, and no one was willing to take responsibility for carrying out his orders. The retired shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu was consulted, and counseled lenience. So it was that in the tenth month of 1609, Nakako was among the group of former imperial concubines banished indefinitely to the tiny island of Niijima off the eastern shore of Japan in the Pacific Ocean….

Nakako is the only woman involved in this scandal whose life can be traced—“documented” perhaps overstates the case—from birth to death. When I began researching her story I thought that I would eventually be able to tell at least part of it in her own words, but I was wrong. Unfortunately, nothing indisputably by Nakako herself—not even a poem—has survived. The material I did find straddles the worlds of fact and fiction: it includes oral history, poems, and a seventeenth-century novelette, as well as the more usual diaries, letters, and official histories. My aim in this book has been to convey something of what it might have been like to be a woman in Nakako’s world—without making anything up.

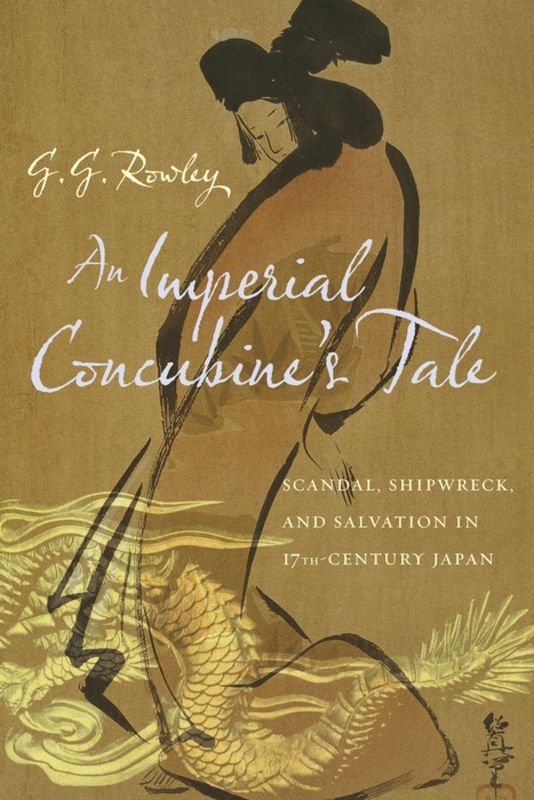

For more about the cover of the book, click here.